This is a brief overview of the paper Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the Hippocampal-entorihnal system

linked here

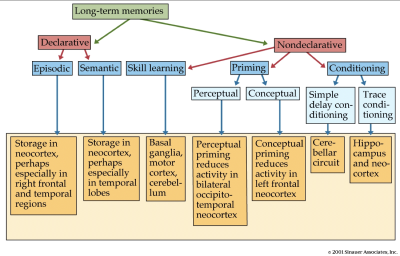

Memory is the core mechanism of any living organisms. The current understanding divides memory into long-term and short-term (working). Long-term memory can be further divide into Explicit (Declarative) memory like facts about objects and places, semantics for language and activities, and Implicit (Non-Declarative) memory like muscle and skeletal response, emotional response, skills and reflexes. We are going to discuss a specific type of long-term memory, the Declarative memory.

Understanding the mechanism has been a challenge that Neuroscientists have finally gotten a breakthrough in, this paper summarizes all findings and provides a comprehensive insight into the current understanding of how spatial memories are formed and recalled in the brain. The paper proposes that mechanism of memory and planning has evolved from mechanisms of navigation in the physical world. They hypothesize that the neuronal algorithms involved in real world navigation and mental space are essentially the same.

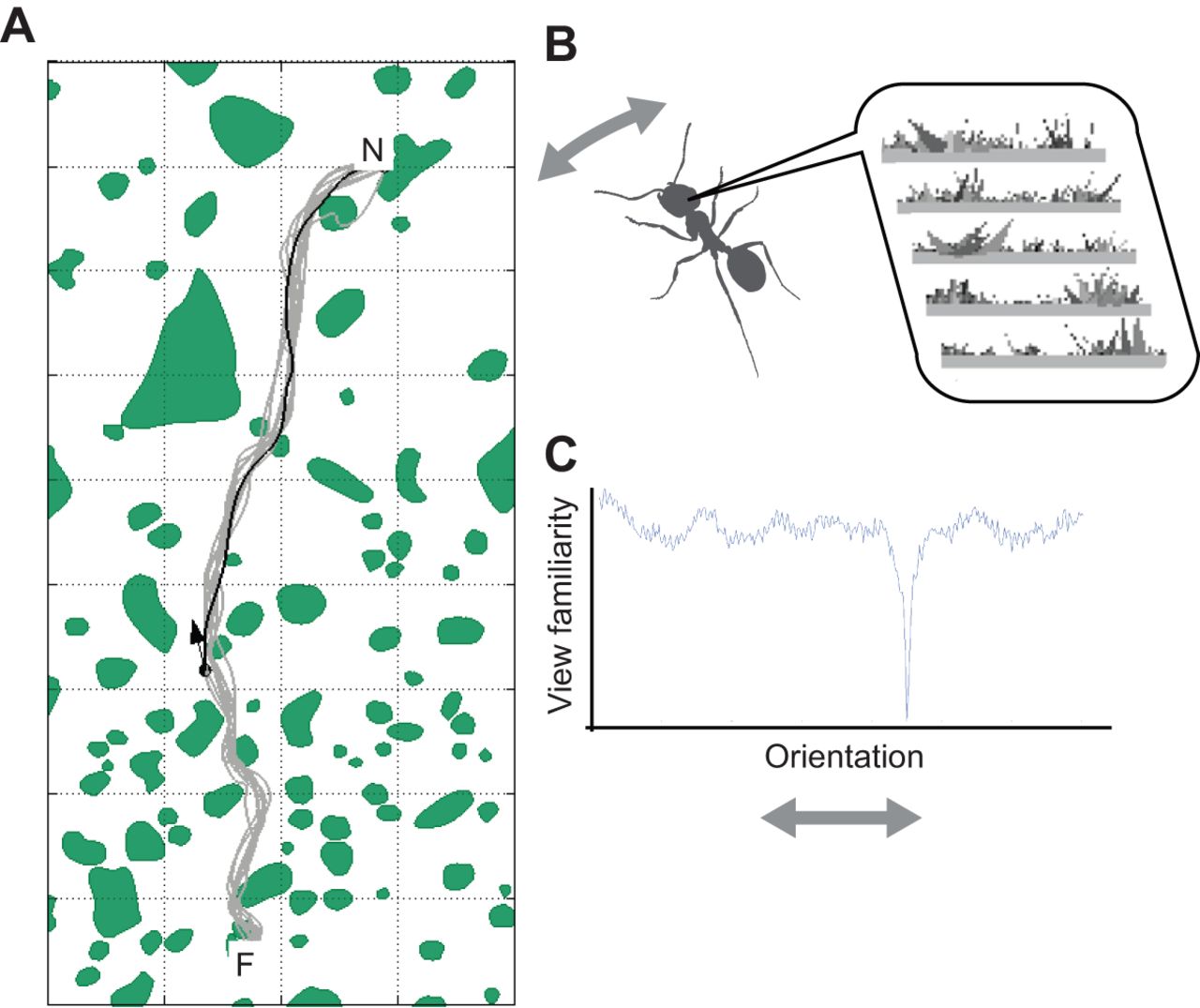

When an animal moves around in an environment, the current static position in reference frame is the first thing required, called map-based (allocentric) navigation which uses the spatial relation of landmarks to define the relative position in the environment. Also, a second way of calculating position based on integration of motion with knowledge of previous position called path integration (egocentric navigation) which also helps measure distances of and between landmarks. In exploring the surrounding any of the two navigation methods may be dominant depending on the environment. For instance, if there are lot of landmarks or objects in a relatively large are, it’s better to rely more on the allocentric way. But if the path is narrow and has no obstacles in the way, egocentric navigation is the only way to proceed exploring.

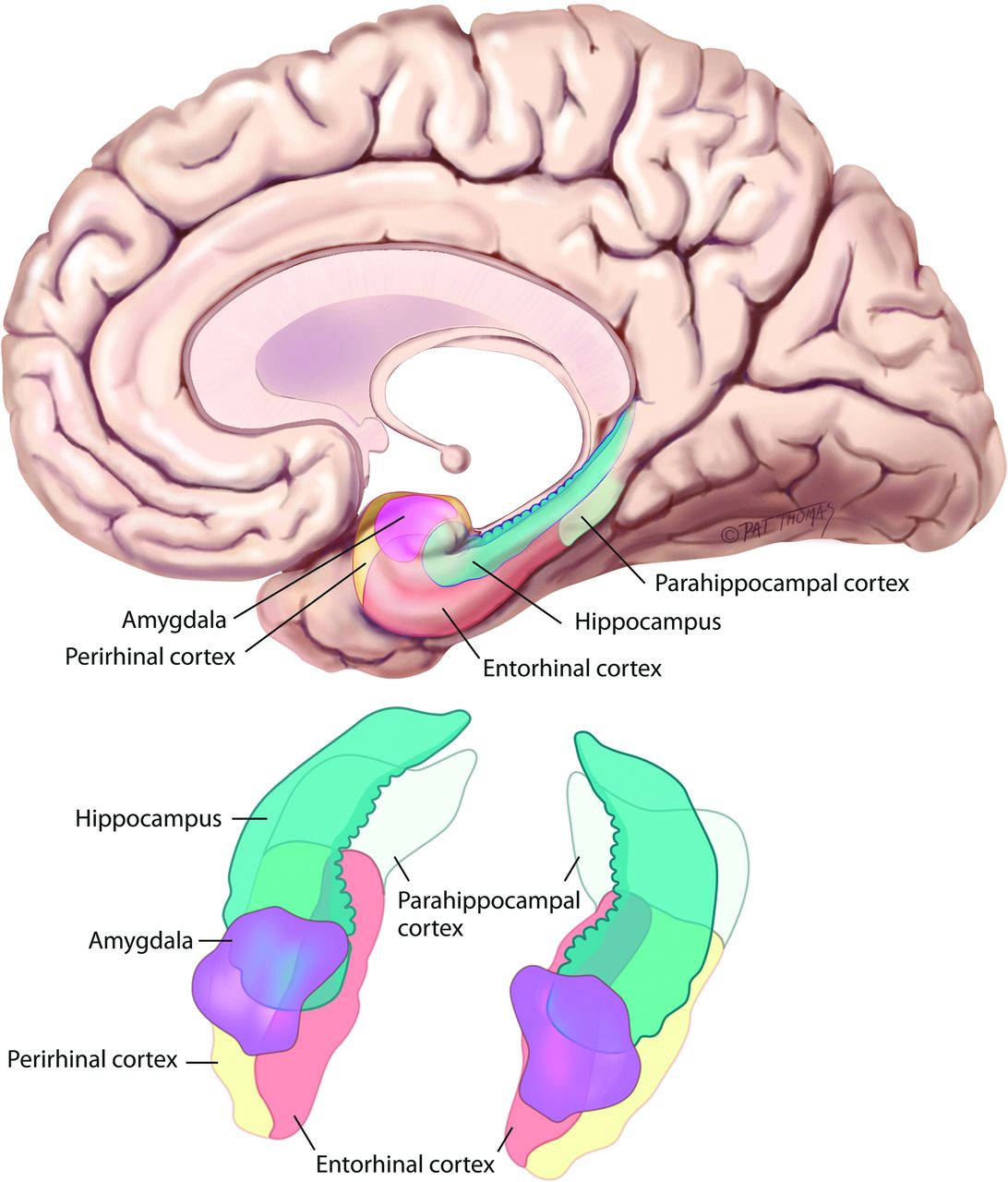

The two main regions of the brain that were discovered to be responsible for declarative memory are the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex.

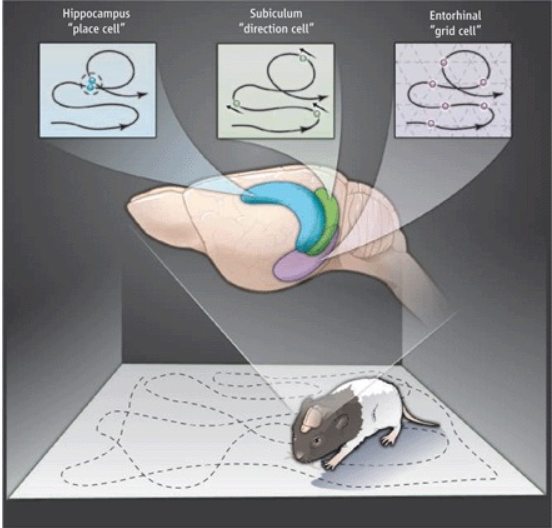

The entorhinal cortex consists of grid cells, in geometric formations that are packed at different spacing along the vertical axis for neural representation of space, head cells which are responsible for directional reference frame and boundary cells that assist in allocentric distance triangulation. These help in accurately representing a map of the surrounding and the reference point giving rise a structure that is ideal for computing spatial metrics irrespective of the environment and the arrangement of the grid cells are such that variations of maps when there is change in the surroundings is also possible. This nature of the entorhinal cortex can be combined with the place cells of the hippocampus to form a vast number of individualized maps for various places visited over a lifetime.

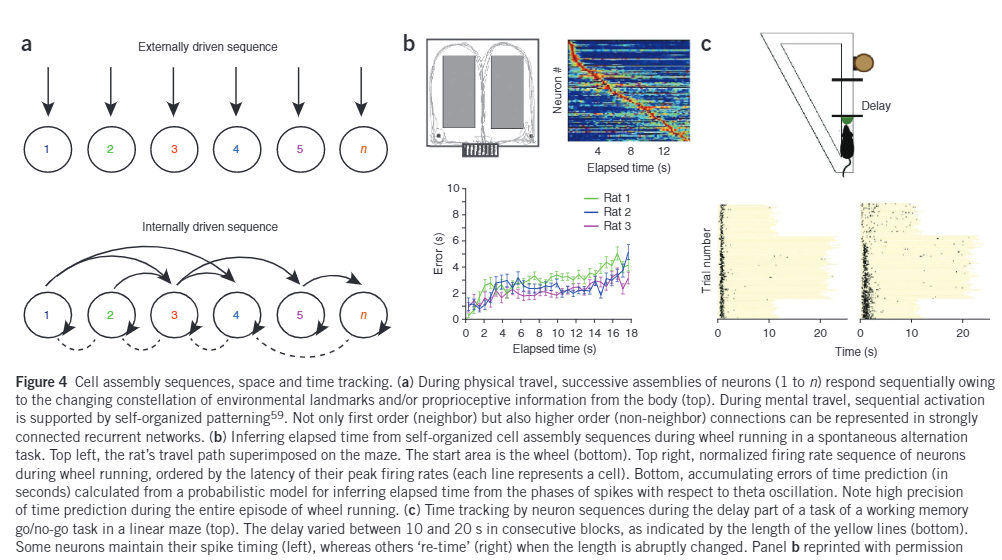

It is easy to see how this mechanism could not only be used just for measuring physical space, but also distance between other forms of information. Keep in mind that the hippocampal cells are active at random and may change based on subtle changes in the high-order grid pattern representation of the environment received from the entorhinal cortex. Together the mechanisms of these two regions allows storage of very large number of arbitrary associations without interfering with one another. Below in part (c) of the figure shows an experiment in which the rat is made to run within a maze or stop based on a cue. (a) part of the figure shows how the sequence of neurons fire during creation of the path through the maze. Subsequently the lower half shows how the recall or future path planning causes firing of neurons. The experiment shows several interesting results. A time interval between 10-30 microseconds between the cue and go can create slightly varying representations in the rat’s brain. Furthermore, after the rat has been running in the maze for a while, sudden changes in the spatial representation occur, this might be either due to generalization allowing the rat to predict (imagine) future path, a ‘mental jump’ as it was trained in distinct environments and now there is a change it observer. Even physical cues can trigger such jumps. The closer two events are temporally the finer details with respect to the context can be recalled. This is since time and distance are not stored or represented in the brain proportional to actual measurement, but rather is circumstantial, so the longer an episode runs, the more summarized it becomes.

The above two figures demonstrate the use of grid cell modules to represent accurately the environment chunk within an episode. These kinds of properties are resultant of the theta cycles that allow grid cells and place cells to synchronize and encode information in the sub-theta lags created by the 30 microseconds window within a chunk of an episode. This allows representation of same distance or time in the real world in different contexts. The cycle not only compresses first-order sequence of past and present positions but can also recall chunked up parts of the environment without actually visiting all points. This mechanism gives a flexibility in path planning and enhances episodic memory. Hence there can be an infinite number of paths imagined from start to finish of a journey similar to which a story can be recalled in several ways connecting the beginning and end through innumerable variations. The conclusion is that it can be hypothesized that the mechanism involved with optimal path selection for navigation in the physical world can also find the optimal selection of sequence of parts in an experienced memory as episodic recall are rarely accurate representation of true sequence.